Ann and William Oppenhimer, Virginia - MEET THE COLLECTOR Series Part Forty Nine

I’ve known about this week’s collectors for a long time and I am an avid reader of Folk Art Messenger, so it was a real treat to interview them. Ann and William Oppenhimer have been collecting folk and outsider art for many, many years and set up the Folk Art Society of America in 1987, which is still going strong. They had a wonderful friendship with the artist Howard Finster when he was alive, so read on to hear more about that and how they built their collection over the years, in part forty-nine of my ‘Meet the Collector’ series.

Ann and William Oppenhimer by Taylor Dabney

1. When did your interest in outsider/folk art begin?

Ann: In 1973, I started collecting the small animals and birds carved by Miles Carpenter. Some friends and I would go to visit him just because we enjoyed being with him and seeing what he was making. He lived in Waverly, Virginia, about 45 minutes from Richmond. In 1980, I bought my first Howard Finster painting, “Herbert Hoover,” when visiting Finster’s dealer at the time, Jeff Camp, in Tappahannock, Va. My son, then16 years old, said, “Go back, we can’t leave that painting there.” So I turned around and left a note to Jeff that we wanted to buy the painting.

William (“Boo”): My interest began when I married Ann in 1981. Right before we married, we took a class in Contemporary Art History together.

2. When did you become collectors of this art? How many pieces are in your collection now, and do you exhibit it in your home or elsewhere?

Ann: We didn’t consider ourselves collectors until we returned from our first visit to Howard Finster in 1983. We bought 50 pieces from Howard on that trip, and our lives have never been the same. We keep our collection in our home. We have donated 375 pieces of art to Longwood University beginning in 2007. Last year, in October 2019, Longwood University dedicated the Oppenhimer Folk Art Gallery on the campus, which currently displays 52 works from our donation.

Boo: My path of significant collecting began with our trip to visit Howard Finster. Part of my interest was as a fan of late night TV show host Johnny Carson. Howard was scheduled to be on The Tonight Show the following Monday, and I knew he would be famous after that. My intent was to buy as much of his art as we could pack in our minivan, as opposed to Ann’s being more selective. As Ann said, much of our collection has been donated to Longwood University and other museums. The folk art has taken over all the other art in our home.

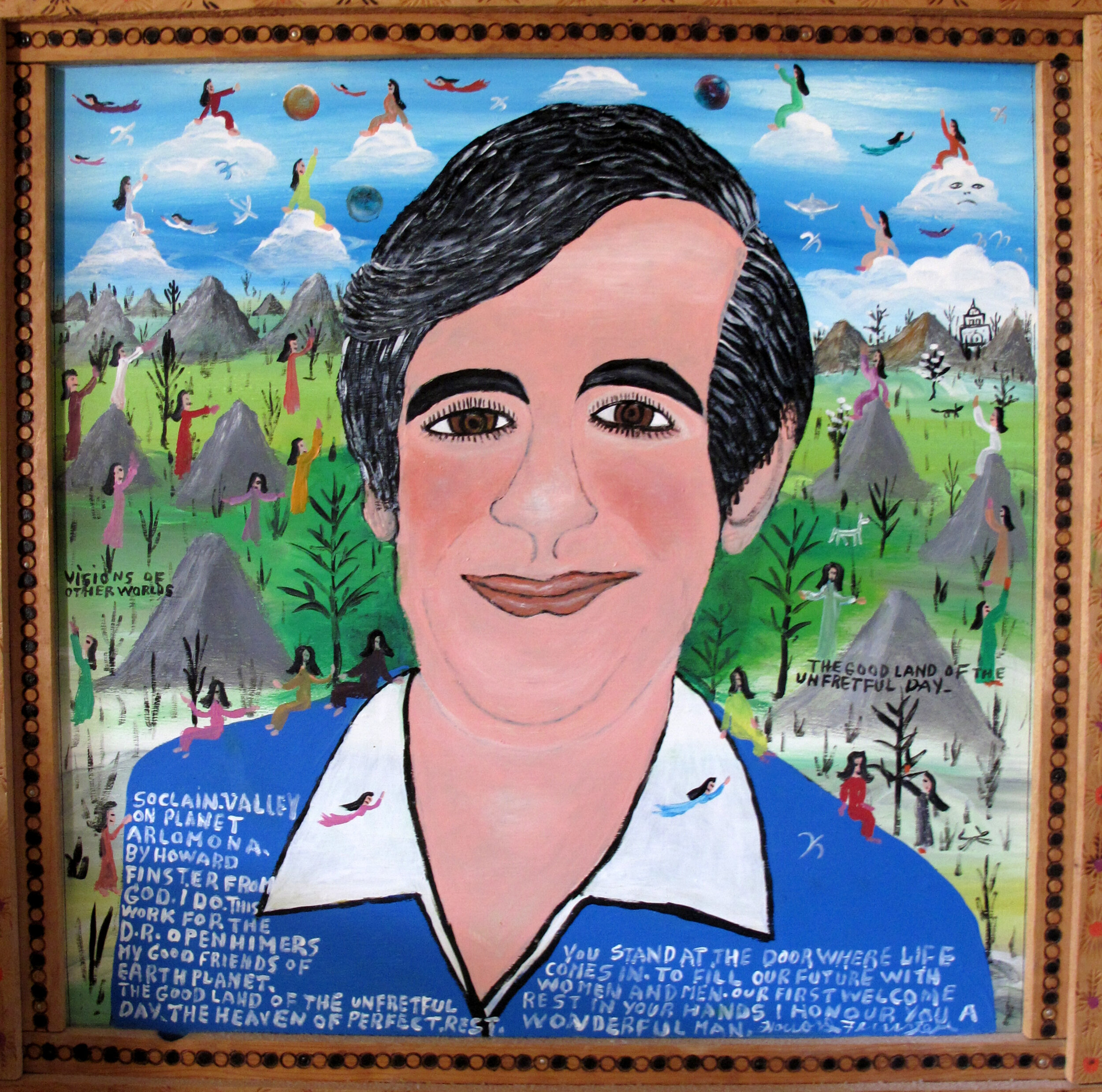

‘Boo’ by Howard Finster

3. Tell us a bit about your backgrounds.

Ann: I majored in Biology at the University of Richmond because my parents would not let me go to art school. When my youngest child went to kindergarten in 1970, I decided to get my master’s degree in Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. After five years as a part-time student, I graduated and immediately got a job teaching Art History at the University of Richmond, which I enjoyed until I retired in1992. As a child, we had virtually no art at home, except for the paintings I did.

Boo: I graduated from Hampden-Sydney College and the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Then, I served in the US Army in Germany as a physician, attaining the rank of Captain. Returning to Richmond, I took a residency in OB/GYN at the Medical College of Virginia, and practiced OB/GYN from 1960-1990. Before we were married, I did not have an active interest in art, but Ann says I was a quick learner. Years before, I had taken a drawing class with Nancy Witt, a well-known Virginia artist. A friend gave me a small duck carving, and I since have continued to collect the work of that artist. My parents had portraits by Thomas Sully and Saint-Memin at home, but my background in art was meager.

"Woman with a Dog" and "Blue Jays" by Miles Carpenter, Virginia.

4. You both founded the Folk Art Society of America in 1987. What drove you to set this up?

Driving back from our first visit with Howard Finster, Boo said, “Why don’t we get Howard to come to the University of Richmond and have an exhibition of his work and put on a festival?” So we began working on that project, and one year later, in October 1984, “A Howard Finster Folk Art Festival” became a reality. Boo named the exhibition, “Sermons in Paint,” because Howard had given up preaching after his congregation confessed one evening that they did not remember what his morning sermon had been about, so he decided to preach through his painting.

We contacted people who knew Howard – scholars, collectors, writers and friends, and this ended up involving about 200 people. Borrowing art from various sources, we made contact with other collectors and museum personnel. During that week, Howard stayed in our home, and we were with him through workshops, musical performances, meals, lectures and the exhibition. After that, our life really was never the same!

In 1987, we decided to get a group together in our home to talk about forming the Folk Art Society of Richmond. This quickly changed to forming the Folk Art Society of Virginia, and then Boo said, “Let’s make it the Folk Art Society of America.” Ann wrote to the 200 people we had become acquainted with during the Finster Festival, and most of those people joined the Folk Art Society of America. We received small grants from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and from the City of Richmond, and that helped to get us started.

Assorted Animals by Linvel and Lillian Barker. Kentucky.

5. The society is still going strong today, as is the magazine, Folk Art Messenger. What do you think has kept people’s interest all these years?

The Folk Art Society is a non-profit organization, and we have never taken any financial compensation for our work. The society has sponsored national conferences with benefit auctions for 30 years in many exciting cities throughout the United States. We offered a program of speakers, visits to museums and private collections, including social activities, and that attracted members. The Folk Art Messenger is one of only two such remaining publications in English, and we continue to have remarkable and talented writers and photographers who contribute their work to the Messenger. We also employ a creative designer, who does excellent work. We focus on the artists and strive to put their careers and interests first, and the artists tell us that they are appreciative and that they consider our publication essential to their livelihoods and success.

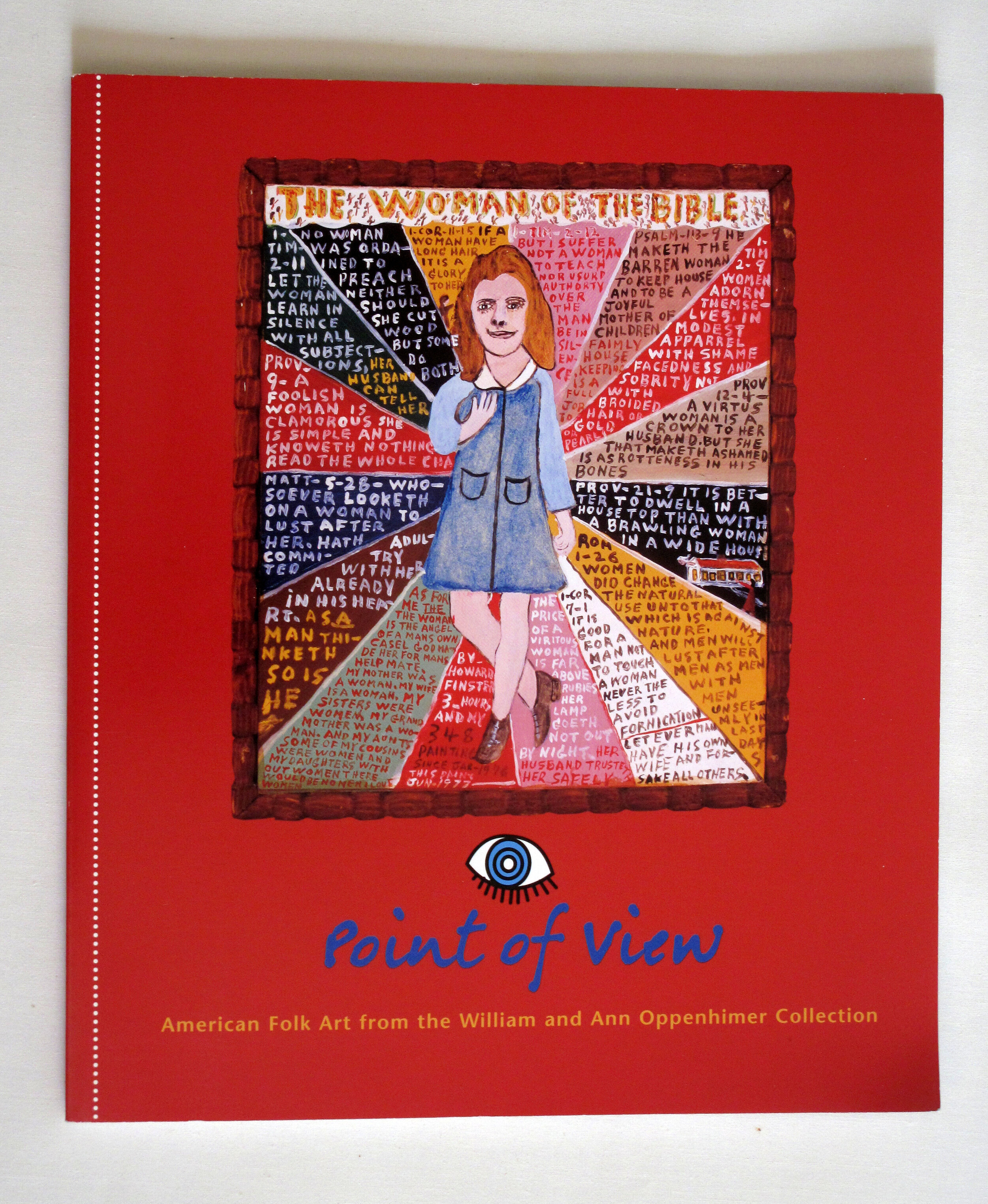

6. How did the exhibition, “Point of View: American Folk Art from the William and Ann Oppenhimer Collection,” come about? And what led to your decision to want to share your collection?

Frank Holt, then the director of the Mennello Museum of Folk Art in Florida, asked if we would lend our collection to his museum, but he became ill and unable to carry it through after talks had begun. Then Richard Waller, director of the University of Richmond Museums, said he would like to originate the exhibition there, and we began to work on it with him.

He asked us to take photographs and make a list of the pieces that we thought would be good to exhibit. We selected about 180 pieces, and Richard came over to discuss it. He said he thought about 50-60 pieces would be a good number, and Ann said, “Richard, we have more than 100 pieces of art in our living room!” Richard said, “But we don’t want the exhibition to look like your living room!” We compromised on 86 pieces. The University of Richmond published a beautiful catalogue.

“Point of View,” after opening at the University of Richmond, traveled to seven more museums during a period of four years, 2001-2004. In addition to the art, we also featured photographs of the artists and a short biography of each artist as part of the exhibition.

If you accumulate a sizable collection, it’s rare to have enough space to display it, and sharing it is the most interesting way to do it. It’s fun. It also helps the artists. Once you have this art, you would like for others to enjoy it. Museums seldom rotate their stock, and neither do we at home, except while pieces are loaned out for exhibitions.

"Point of View," Exhibition Catalogue. Cover Image: "The Woman of the Bible," 1977, #348, by Howard Finster.

7. Do you ever loan pieces from your collection to other shows? What would make you want to do this?

We have always enjoyed sharing our collection with others, either at our home or in museum exhibitions. It promotes the artists and gives them the recognition they deserve. It gives pleasure to others as well as to us. It is exciting and a real honor to be able to show our collection. Works from our collection have been shown in more than 80 exhibitions, but only three of these were exclusively from our collection. It’s a great avocation. We have never sold any of our art, but, to date, we have donated more than 400 pieces to various museums.

8. I read that your mission in collecting was to meet all the artists that you collected. What kind of places did this take you to? Are there any particular visits that stand out to you?

Yes, from the beginning we were as interested in the artists as we were in the art, in fact, perhaps more so. Almost every piece in our collection was either a direct purchase from the artist or a gift. We have visited many of the artists in their homes. Many of them became dear friends, and we attended their weddings and their funerals over the years. We were not able to meet quite all the artists because several had died, but because of this questionnaire, we made a list and discovered that we have met and made friends with more than 100 artists.

Propinquity is always an influence, and consequently we have a lot of art from Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky artists. Probably one of our most interesting trips was a two-month camping trip we took across the United States in 1990, after Boo retired from his medical practice. We drove more than11,000 miles. We planned to camp in a dome tent in national parks and to visit artists, collectors, museums, and members of the Folk Art Society. Because one of our daughters lives in Oakland, we have a lot of art from California, especially from Creative Growth, Creativity Explored, and NIAD. We love Santa Fe, and we have visited there many times, getting acquainted with the artists in the area. When the Folk Art Society conferences were held in various locations we met and visited artists, who often took part in the program or exhibits.

It has been a remarkable experience and a source of great pleasure to meet the artists. Taking a history is part of medical practice, and Boo enjoys interviewing the artists while Ann documents the visit. These oral histories are part of the Folk Art Society’s archives, which are now in the collection of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture in Richmond.

"Head of a Man," Face Jug, by Lanier Meaders, Georgia.

9. Can you tell us about the special friendship you had with Howard Finster over the years?

We first met Howard in 1983, the weekend before he was going to be on the Johnny Carson Show. We were not able to obtain his address or telephone number until Boo was rearranging some paintings and looked on the back of “Herbert Hoover” to see that Howard had written, “My Earth Phone, please call.” We called him and drove the 10 hours to meet him. We had a special bond after our experience of having him stay in our home for a week during the “Sermons in Paint” festival in 1984.

In 1985, Ray Kass, an art professor at Virginia Tech, planned a “Work-Out” with Howard for his students and local people. He told me that Howard would be staying at a cabin at Mountain Lake, part of Kass’s yearly Mountain Lake Symposia. I said, “What is Howard going to eat, there by himself?” Ray said, “I’ve laid in some food for him.” I said, “Well, a friend and I are going to come up there and cook for him.” We did, and we stayed in the cabin with Howard for a week, helped with the workshops and made art with Howard and the students – another unforgettable experience.

Most of our children have visited Howard at one time or another, and they collect his work. We made many trips to Summerville, Georgia, over the years. Whenever he was going to be as close as Washington, D.C., we went there to be with him. We talked frequently with him on the phone. Howard was a loving person, who used to say, “I never met a person I didn’t love,” and we were fortunate that his love was shared with us.

Howard Finster is the reason that the Folk Art Society of America exists. Without our contact and friendship with him, there would be no Folk Art Society and no Folk Art Messenger.

10. What type of art work, if any, is of particular interest to you?

We seem to have a lot of carvings, especially of animals and birds. But of course we love paintings, drawings, ceramics, baskets, quilts, and face jugs. Howard made paintings, assemblages, cut-outs and sculptures, and we have an assortment of these from different time periods. We especially like the set of Finster serigraphs that he made with Virginia Tech alumnus Brian Sieveking. These were all designed by Howard, and he drew the patterns and chose the colors, while Brian actually pulled the sheets.

"Herbert Hoover," 1978, #1,282, by Howard Finster. Georgia.

11. Do you each have a favorite artist or a piece of work in your collection, and why?

We have to say that Howard Finster is our favorite artist because of our long friendship. But, I have many favorite pieces – by Howard of course, but also by Jon Serl, Nick Herrera, Bessie Harvey, Eldridge Bagley, Minnie Adkins, S. L. Jones, Jim Harley, J. J. Cromer, and the Indian artist Pradyumna Kumar. I look at them every day. Boo’s favorites are the animal carvings of Linvel and Lillian Barker. We display the Barkers’ sculptures in our living room in a bookcase painted by an artist (not a folk artist) friend.

12. Is there an exhibition that you feel has been particularly important and why?

“Passionate Visions of the American South” was an important exhibition for us. We went to the opening in New Orleans in 1993, and many of the Folk Art Society members were there with items from their collections in the exhibition. The Folk Art Society conference was part of this event, and artists, collectors, and museum officials were there, some that we met for the first time.

“Black Folk Art in America” at the Corcoran Gallery of Art was probably the most important exhibition in that many of those artists were first introduced to the world through this ground-breaking exhibition. However, we did not see the exhibit, because it was in 1982, before we really got involved.

The Souls Grown Deep exhibition at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta was another important exhibition as it was the beginning of Bill Arnett’s presentation of the African American artists who now, through Arnett’s efforts, have been acknowledged as some of the most important American artists. We made a special trip to see that exhibition of 450 works from Arnett’s collection. We greatly admire what he did to document, exhibit and promote these artists, whose work has been acquired by more than 20 mainstream fine art museums, though the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Personally, in 2011, the exhibition of our collection at Longwood University, “Three Ring Circus,” which displayed 278 works of art and was curated by Kathy Johnson Bowles, was an amazing honor for us, as was the award-winning catalogue that accompanied it.

"Feeding the Cows" by Eldridge Bagley. Virginia.

13. What people in the field do you feel have paved the way for where the field is now?

In the beginning there was Herbert “Bert” Hemphill, who we were fortunate to know and grew to admire. His collection made people aware of an art that was different. He was always generous with those who wanted to see his collection, including us, when we were complete strangers. He was a strong supporter of the Folk Art Society from its beginning, one of the original National Advisory Board members. He attended every conference from the first one in 1988, when he was the featured speaker.

Chuck and Jan Rosenak through their collection and their important books were great influences and distributors of knowledge and facts, especially concerning Native American and Hispanic artists.

Bill Arnett, as we have said, was one of the great champions of African American artists of the South, through his exhibitions and his books and through the formation of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

14. Where do you buy most of your art?

We have bought most of our art directly from the artists. We have probably bought no more than 12 works from auctions, except for those we bought at the Folk Art Society’s annual benefit auctions, where the art is donated by members and artists. We never like to buy anything at auction unless we have examined the work personally and are familiar with the artist. We have bought probably no more than16 pieces from dealers, although dealers often have the best pieces. We’re not very good customers, but we are friends with several dealers and recommend them to others. We like to buy artworks from centers for the disabled, and we always try to meet the artists when we do so.

15. What is your opinion of the term, “Outsider Art?”

We are not great fans of the term, “Outsider Art.” We do not think the artists enjoy being outside, and many have expressed this to us. However, the term is popular anyway. Boo coined the term, “Intuitive Art,” for an exhibition at Virginia Tech. Since we call our organization and our publication by the name “Folk Art,” we are not about to change the name, although this term is becoming less and less popular.

Untitled Sculpture by James Harold Jennings, North Carolina.

16. Have you managed to persuade many friends to become interested in this field, and what do they make of the art in your collection?

We have made many new friends who also collect the same type of art as we do, and those friends have enriched our lives. One couple that we were close friends with, began visiting James Harold Jennings and collected his work, and another couple began to collect quilts when we suggested they needed something for their bare walls. But most of our old friends have not really responded to this art, including some of our own children. Visitors often ask, “Where did you get all this stuff? And did you make it?”

17. Is there anything else you would like to add?

We have enjoyed meeting artists from many other countries. We went to India specifically to meet Nek Chand, and we were at the Rock Garden in Chandigarh for five unforgettable days with him. We went to Cuba to meet the artists there, and we still remain in contact with the Cuban friends we made. Ann visited Mexico and Nova Scotia and met the artists and art collectors in both places – wonderful enriching experiences!

We spent part of 17 summers in the South of France, where we met many artistes singuliers, as well as the notable scholar, Jean-Claude Caire, who died recently. These French friendships were all due to the generosity of John Maizels who introduced us to these artists. John has made a marvelous contribution to the history and promotion of self-taught art through the publication of Raw Vision magazine as well as his outstanding books.

In America, self-taught art is gaining a foothold now as the result of a shift in emphasis to diversity and inclusion, which features art by Black and brown artists. In our collection, we don’t classify artists by their skin color. We like art from African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic Americans, Oriental and Indian artists, as well as white artists.

"Mother and Son," 1990, by William Dawson, Chicago.