BILL SWISLOW, CHICAGO – MEET THE COLLECTOR PART SEVENTy

Part seventy of my Meet the Collector series, Bill Swislow, who lives in Chicago. He has most recently been documenting the fascinating anonymous carvings that line the lakefront in Chicago, and these have now made it into a book. He has donated a huge amount of works (around 700 pieces) by Joe “40,000” Murphy to the John Michael Kohler Center in Sheboygan, which we hope to see turned into an installation in the future. Read on to hear about his electic tastes, how he went from advertising cars to art, and the website he continues to update, mostly now about the carvings.

Bill Swislow, taken by Janet Franz. The images behind Bill are photographs he has taken.

Jennifer: Bill, what is your background?

Bill: My background is not that interesting. I mean, I grew up in suburban Chicago, very normal 1960s-era upbringing. My professional background is in journalism and media, and not art. I grew up pretty much without art being part of the environment, that came later in life, like high school, mostly through a friend of mine who was very passionate about art and architecture and kind of opened up that world to me, at the time.

Jennifer: Great, so this is why I wrote the second question - that you run cars.com, which seems so far removed from journalism, or from art or from anything else? Why?

Bill: Well, you know, not because I was a car guy. I wish I had been; it would have been more fun. Well, you know, it's not really far removed from journalism. I worked at a variety of newspapers and other media around the country but wound up at the Chicago Tribune in the 1990s and was working on the newspaper as an editor. But in 1994/95, the Tribune started ramping up its online presence. It actually started a couple years earlier. But I moved over from the newspaper to the online part of the Chicago Tribune in 1995. And early on, the folks at the Tribune realised that the internet's biggest implication was going to be, at least economically financially for them, was around classified advertising. In the United States, anyways, it was the primary driver of profitability of newspapers. Classified ads, help wanted ads, cars for sale ads, were insanely profitable. And so, I got the task at the Tribune after doing other work on the more general website of the newspaper, of moving their classified advertising products online. So, I did that. And then the Tribune became a lead partner in a newspaper consortium to launch national classified advertising sites. So, I was assigned to work on that. And the first new site that we launched was cars.com. And I just kind of stuck with it after that. But yeah, that's how I wound up @cars.com.

Jennifer: So, nothing to do with you being a car fanatic, and being obsessed with them! Ha!

Bill: Not at all. I hired people who were. So, we had a lot of car guys working for us. I mean, I had some interest but pretty minor.

Jennifer: I guess you kind of came to contemporary art first. So, when did you come across folk outsider art?

Bill: I had a pretty good interest in contemporary art, art museum art. But at the same time, I did have a sort of a parallel interest in vernacular art and in sort of kitsch and pop culture. Actually, early on, before I got interested or knowledgeable about outsider art, I was very interested in roadside art and architecture, from the late 1970’s. So, it was sort of this parallel track, right? But I had very little awareness of outsider art or folk art even though in 1979/1980 I used to go to Phyllis Kind’s New York gallery a lot. But I went there to see the Chicago Imagist’s work she was showing, not Howard Finster or Martin Ramirez. I mean, I'm sure I saw that stuff there. I remember seeing Henry Darger at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art in 1979. But it didn't click with me, it was just interesting, but nothing that I could get serious about.

So really, my first interest in [owning] art was thrift store art, which I started acquiring in the early 1980s. But again, I didn't really connect it to Howard Finster or Jean Dubuffet. Even though I had heard of the “Museum of Insane Art” in Lausanne (that was how it was described to me), I didn't really know anything about it. But, at some point, when I got a little older, I thought it'd be nice to have more than just posters on the wall, and I got interested in acquiring art, but I found that contemporary art was basically not affordable. I mean, even small drawings by relatively young unknown artists were too expensive for me. I did buy some art from a friend of mine, who was a trained artist and ended up being very successful. But around 1988, I had moved back to Chicago. And I met people who were acquiring southern folk art. They kind of led me, and this stuff was affordable, aside from being interesting. So, it kind of jibed with this other interest I had - with sort of thrift store art, and folk crafts, because I was collecting bottlecap figures at thrift stores and flea markets and sock monkeys and things like that. So, it kind of fit in with that. But then once I discovered it, I became much more interested in it. And I made a number of trips through the south to that whole circuit, visited Mose Tolliver and Howard Finster and Jim Sudduth, R.A. Miller people like that. And I could afford the work.

The Gyros Project on interestingideas.com

Jennifer: Do you still have that work now?

Bill: For the most part, I do. What I have on my walls is, is pretty widely mixed. I have a few Tolliver works and Sudduth’s on the wall, an R.A. Miller or two, but a lot of that, I have to say, is in storage, in my basement and on shelves. You know, I acquired a lot of it. I've been selling off some of it slowly, just to sort of thinning the herd.

Jennifer: Did you go to these people's houses with other people or by yourself?

Bill: Both. You know, the first visit was with a girlfriend who had done this with her former boyfriend. And it was her collection that kind of opened my eyes to this world, that you could actually acquire this stuff. Jim Sudduth’s I visited a few times, usually with a friend, I think maybe once on my own. But I have to say, I missed an opportunity. There are folks like Jim Arient who really developed relationships with a lot of the artists they visited. And , I'm not that sociable.

Jennifer: Jim's got personalised pieces hasn't he from Howard Finster! Have you got any stories?

Bill: I had a relationship with a couple of Chicago artists, but Lee Godie was not one. When I worked in downtown Chicago, I used to see Lee a lot. This was later in her life, in the 90s. I used to see her, and she'd be selling her work. But I actually never bought any. I was somewhat intimidated because of the stories I heard about her. And so I never acquired any work from her. I ended up with some Lee Godies that I bought at Maxwell Street. You may have heard about Maxwell Street? It was, for people collecting this kind of art in Chicago, just the wonderland.

Jennifer: No one has mentioned Maxwell Street I believe - was that a gallery?

Bill: Maxwell Street is really important. It's been around in one form or another since the early 1900s as just this flea market. It's where you went, if someone stole your battery or something out of your car, you go to Maxwell Street and you could buy it back - that kind of place. It was very large. For Chicago this was multiracial, famous in the blues community as a place where a lot of blues men would play over the decades. You could get all kinds of interesting items there, like crazy collectible stuff, and usually very cheap. The guy who sold me the Lee Godie’s, I'm pretty sure was a drug addict. The Chicago Imagists famously went there a lot, like Ray Yoshida would bring his students, and Whitney Halstead - the School of the Art Institute’s two teachers, who were so influential on the Chicago scene. Lee Godie’s work has grown on me. At the time, I didn't quite love it that much.

Jennifer: There's a whole mixed group for Lee’s work…some people seem to love it; some people dislike it.

Bill: A lot of people in Chicago own it, I mean, people who aren’t even art collectors, because Lee was such a presence. It was a whole thing to go and interact with her and buy her work. So, there's a lot of it around, but it's grown on me a lot. I like it a lot more now. If I If I knew then what I do now I would have dealt with her. I would acquire some work from her.

Jennifer: You said that you've got some work in your basement, kind of in storage? How many do you think you have all together? Do you have an inventory?

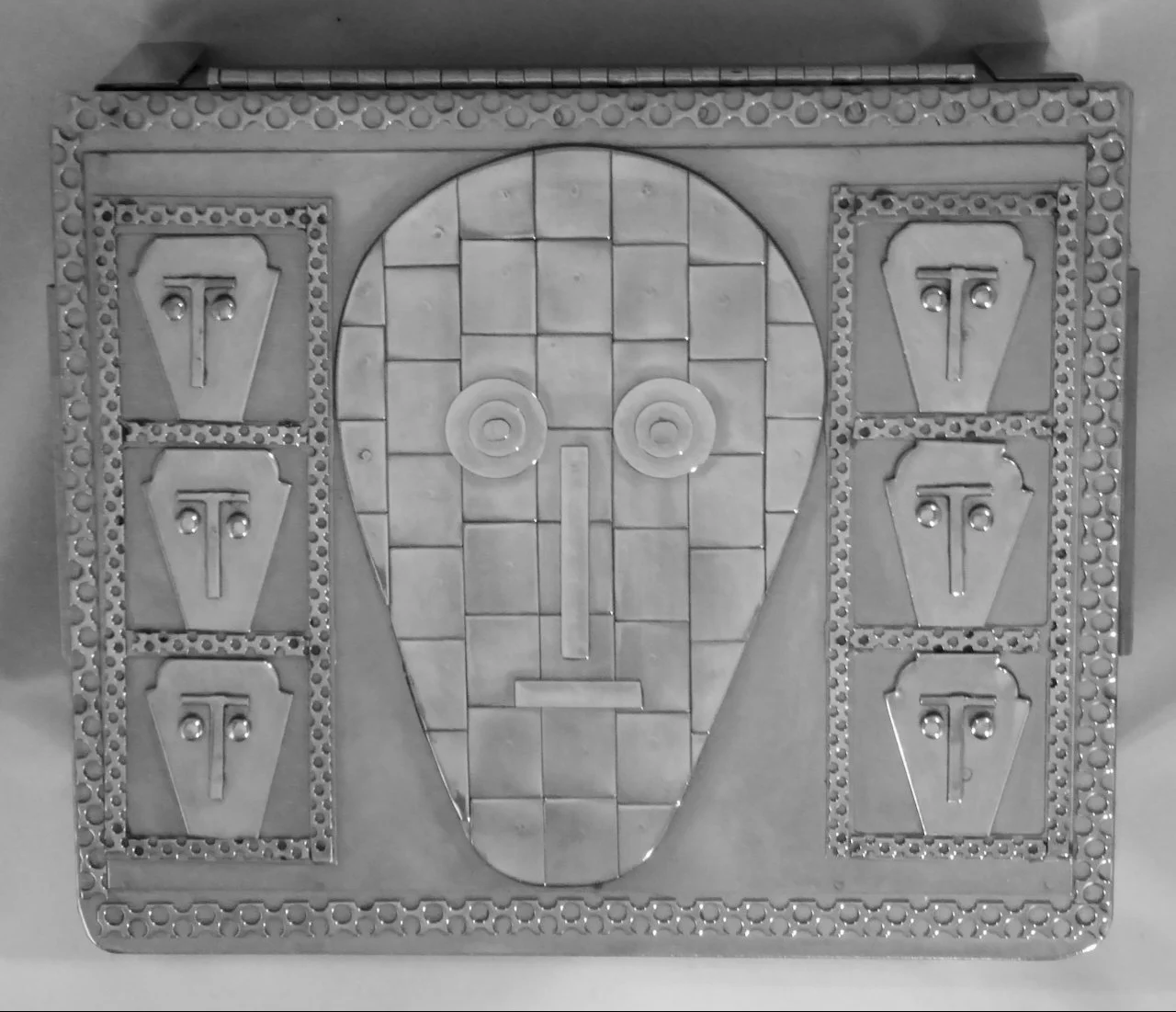

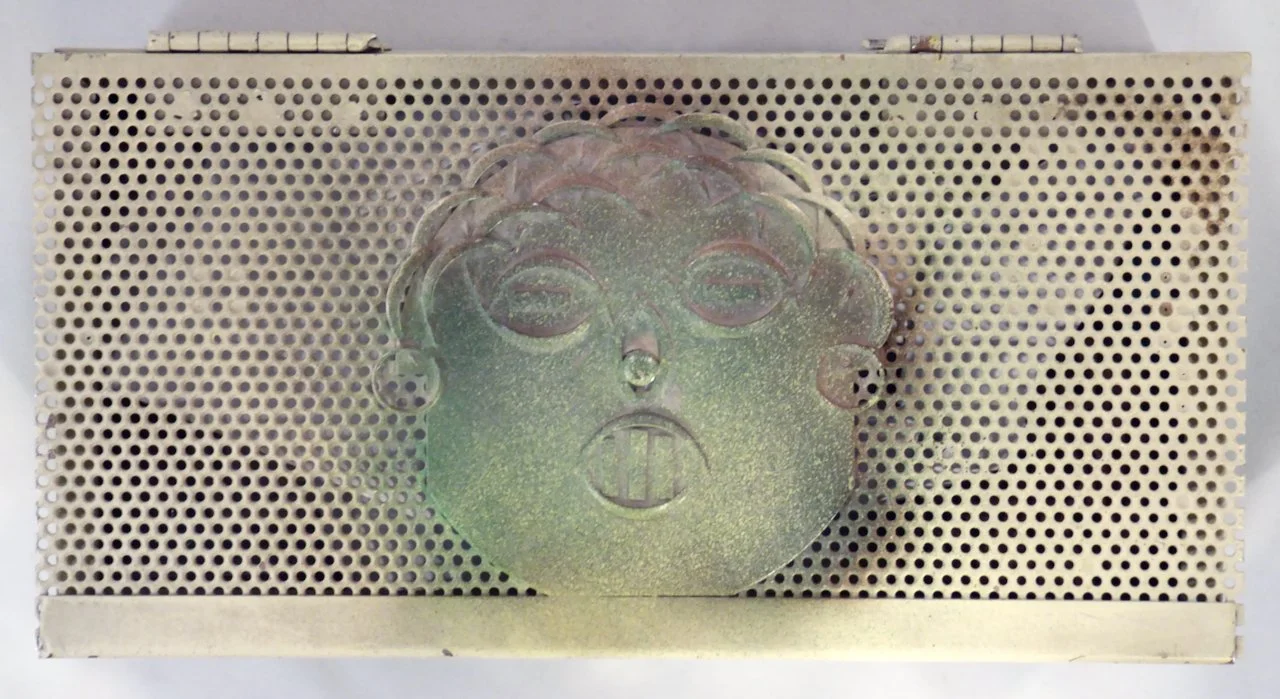

Bill: I do have an inventory. And I think I have about twelve hundred pieces of art in my inventory now. That’s 700 less than I used to have because one of these artists that I collected in depth, I gave the work to the Kohler Foundation last year in Sheboygan. So that was about 700 pieces of art from this photography environment by this artist. Well, he didn't think he was an artist, but an artist named Joe “40,000” Murphy. But now out of those 1,200 pieces, about 200 are bottlecap art, which is one of my other interests. About 450 are pieces of art by Stanley Szwarc, who made work in stainless steel. Stanley Szwarc migrated from Poland, worked at a dental supply company in the suburbs, and would take the scraps and make things from the scraps of stainless steel. Metal boxes is what he's best known for. But also, vases, crosses, all kinds of things. Very prolific. He made thousands and thousands of these boxes. They're very imaginative. All made out of stainless steel, all with his wild decoration.

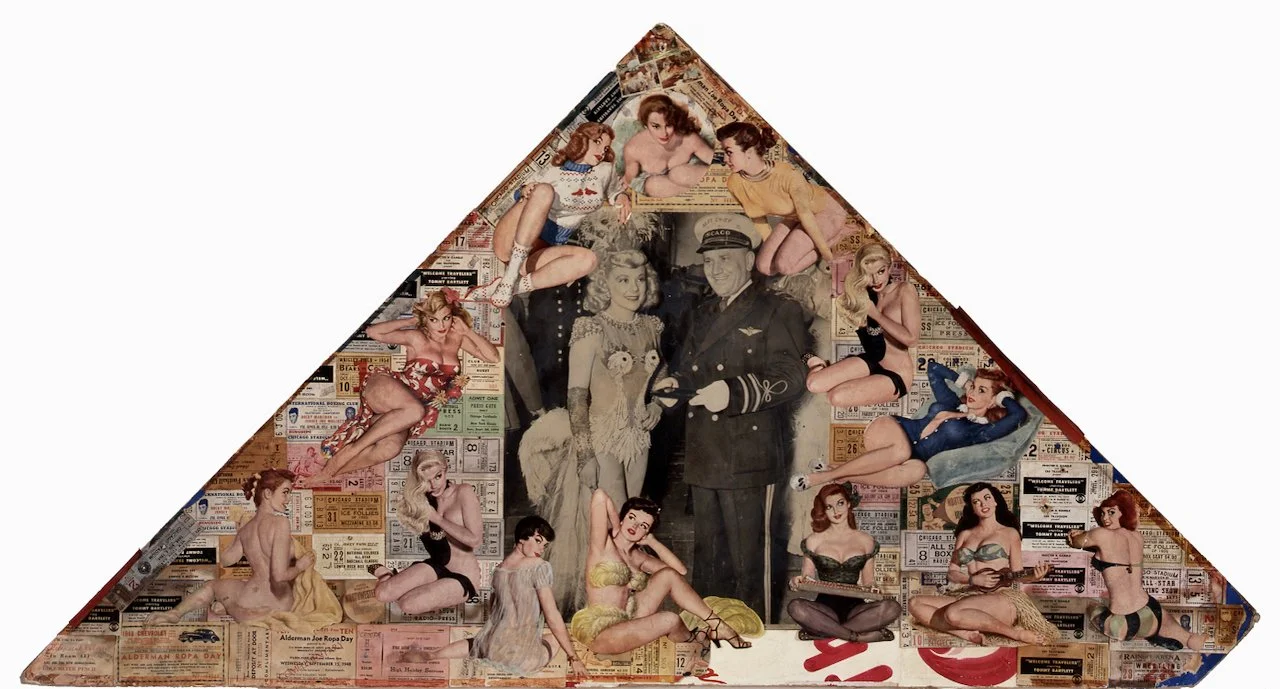

Joe “40,000” Murphy collage with skater and movie star Sonja Henie, early 1950s

Jennifer: How did you find Stanley’s work?

Bill: I found them at a really crappy flea market on the edge of the city in around 1988. He was selling these boxes for about $5 each, maybe $10. Just ridiculously low priced. I got to know him after that and went to see him on a frequent basis in the Chicago suburbs. Every time I saw him, I would buy work from him, partly to support him and partly because I love the work. I knew him well enough that he wouldn't tell me what he wanted for anything I bought, I would have to give the price to him. It was really a burden. I would try to look at what his stuff was selling for in the few places that sold it, and then I would try to give him basically the same amount that he would get if he was selling it to a dealer or a gallery. But Stanley never had a dealer. He was one of the classic cases of a self-taught artist who was never affiliated to a dealer. He overproduced, which we know is what some of the self-taught artists had a tendency to do. His work is sort of in this weird other world, it’s too funky for the craft world but it's also a little too crafty for outsider art collectors, although a lot of people who collect self-taught art out of Chicago have Stanley's work, because he was so prolific. And Intuit used to sell it in their shop.

Jennifer: it seems a bit like Tramp Art kind of thing, and you see that in a lot of people’s houses, but in a way it’s just metal instead of wood?

Bill: It has some of those characteristics of Tramp Art, although more idiosyncratic, or individual than Tramp Art, but they are a sort of accumulation, the cumulative nature of it.

Jennifer: So, would you say that Stanley is your favourite artist in your collection?

Bill: Well, I always struggle with favourites of anything. There's always too many. I love Stanley and I love the Joe Murphy work. I would say they are my top artists as reflected in the amount of work I have by each. There's another artist who you've never heard of, I'm sure. He was named Joe Markevicius, who worked in oils and pastels and was self-taught. I have a lot of his work. He loved to paint buildings and urban scenes, which is one of the kinds of thematic that I love. So, pretty incredible work for someone who was, as far as I could tell, self-taught mostly or entirely. As he would say, these are all buildings that have been torn down.

Jennifer: Are his drawings quite big?

Bill: These vary in size. Three by four feet for some, smaller for others. He mostly worked in pastels. He died a few years ago unfortunately. So, he's another favourite and then the other favourite artist is this trained artist named Sue Williams who is quite successful. If you look her up, you'll see, she has great gallery representation.

I don't buy much art anymore.

You’ve probably have encountered the Woolseys, the Iowa couple? So, I have a small amount of their work. I have one bunny or bear. When I got interested in folk art, one of the first books I read was ‘Made with Passion’, the Hemphill book. And in that book, there’s this picture of him in his apartment. If you look at the bottom, you will see this little bottle cap figure, which I loved. And I thought, why can't I find figures like that? Years later, when his collection went to the Smithsonian, they auctioned off the stuff they didn't want, which included these two pieces, including the one in the picture, which I bought from a Slotin auction.

Jennifer: So, you said that you like collecting large bodies of artworks. So, the stuff you've given to Kohler and this Stanley guy, is there a reason why you like collecting a large body as opposed to like one by each artist?

Bill: Well, believe me, I have a lot of one-offs too. After I got married and had a kid, my wife is not a fan of clutter, so, I really started slowing down my collecting at that point. I tend to go deep in general like if there's an author I like, I tend to read all their books just because it feels like there's more to discover. If you think someone has talent or is doing something interesting, it always feels like there's more to find, more to discover, more to appreciate. So, I would say that’s the main reason. If I like the first piece, then I’ll probably like the second and the third and the fourth. In some cases, as with Stanley and Joe Markevicius, it was also a way of supporting the artist – when it was a living artist I was acquiring work from and giving payment.

Stanley Szwarc face box, 10/14/1998

Stanley Szwarc face box, 1980s

Jennifer: Are you a floor to ceiling hang person with your artwork?

Bill: I'm not. I always wanted to create a room with that Murphy stuff. I always thought it if I had an extra room, I would do that because he had an office where he had rails on the wall that were positioned so he could slide these eight-by-ten photos into the rails and then on the ceiling, he had stapled photos all over the ceiling. So, it was a whole cube of nothing but photos of him with celebrities. I wanted to recreate that, but I never did and that's why I'm hoping Kohler Foundation will now that they have the works. We shall see.

Jennifer: Oh, sounds interesting – let’s see. Loved my trip there a couple of years ago! Is there any artist or artwork that you have always wanted to have in your collection, but you don't have?

Bill: Well, yeah, there's a ton. There's lots of work I would love to have, but I should say, I had a lot of friends who I admire, who if they really want a piece of art, they will sacrifice to acquire it. And I've just never been that way. So, I've always been somewhat cheap about my art acquisitions, never willing to go into debt to buy a work of art. I admire my friends who would be willing to do that. So, there's a lot of work that in theory I could have bought, but it was, from my point of view, out of range. One of the things that I always wanted to have, was one of those carved heads by S.L Jones. But at the time I could have afforded it, I didn't buy it, and then by the time I decided I really, really liked one of those, it was out of the range of what I could easily pay for. The other case like that, the best example was - I don't know if at Bob Roth’s, you saw the Drossos Skyllas presidents that he has? I saw those at Phyllis Kind’s, before Bob acquired them, and I thought those are amazing. This was early on in my collecting and I didn't know who the artist was, I’d never heard of him, I just saw these works. But they were already out of my range. I mean, just more than I was willing to spend. You know, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein too. I have a tiny little Marie photo that I bought in an Intuit auction, but I remember going through those photos at Carl Hammer’s, when, you could have them for a song. In that case, it wasn't so much affordability, I just didn't buy. There's a long list.

Jennifer: You said that you still buy, but not very much to this day. So, what would push you now to buy something?

Bill: It's usually if it's something I'm already interested in. I love bottlecap art. I have a ton of it, but if it’s an unusual one I will get it.

I have plenty of art. I sympathise with those people who say “I don't believe in keeping art in storage,” even though I have a lot of art in storage. So, I don’t want to add much to it, and partly what happened in my own collecting was when I decided I didn't want to keep cluttering the house, I decided what I would do instead is really spend a lot more time finding roadside art to photograph, which is another form of collecting. And so, I've put a lot of time into that, and you'll see a lot of that on my website… me collecting photos of hand-painted signs. I don't collect the signs, I made a conscious choice not to actually try to acquire signs, because that would be counter to my effort to avoid more clutter and more stuff in storage. I take a camera with me wherever I go now. For years, anytime I travel anywhere I have a camera and when I see an interesting sign, I take a picture of it.

Jennifer: Your website is interestingideas.com - how long have you been running this website?

Bill: I created it in 1994, early on. I had been doing a very small circulation, sort of zine-type publication called ‘interesting ideas’ for a few years that I would Xerox and send to friends, and friends of friends. So, when the internet came along, I was very interested in it, so I decided to launch a website to figure out how it worked. At the beginning, I probably had the largest collection of links to outsider art or folk art sites anywhere. I was one of the first people to collect and catalogue all the sites that were there, and there weren't that many. And the same for roadside art. However, I will say that after a couple of years, I realised other people were doing a much better job and were much more committed to that effort. So, I abandoned that, retired the link stuff, but kept the site going and I've kept it going ever since. It's a nice outlet. It's totally under my control so I can put whatever I want there.

Peace rock carvings, Chicago lakefront, circa 1968

Jennifer: So, when you say the ‘carvings’ this is you talking about this book/project which is the lakefront carvings in Chicago? Can you tell us a bit more about this?

Bill: Yeah. it's another one of these areas that fits in with that long standing interest in vernacular expression. And it's a great example of vernacular art, and in some cases you could say folk art, certainly self-taught art. So, Chicago has, unusually for waterfront cities, about twenty-six miles of shoreline, of which about twenty-four of those miles are park, which is really unusual. One of the things Chicago did in the first half of the 20th century was to protect the shoreline from erosion, because all of Chicago’s shoreline is landfill, none of it is natural, or almost none of it. And so, it's subject to really bad erosion. So, they lined it with these big limestone blocks that were quarried in Indiana and then shipped up to Chicago. And so, starting in the late 1920s, when these blocks were put in place, people sitting there started carving them. They started carving names on the blocks, they started carving initials on these blocks. They carved faces on the blocks, they carved, what I call bathing beauties. Really, literally thousands and thousands of these carvings along the lakefront, stretching from the Indiana State Line about sixteen miles north to where I live on the north side of the city. A lot of them were destroyed in the 2000s when the government decided they needed to replace these limestone blocks with concrete and steel, which was a debatable proposition, but that's what they did. And frankly, if Aron Packer, the Chicago art dealer, hadn't started photographing them, there'd be no documentation of a lot of them because I came to it rather late in the game. I was interested in them as examples of vernacular expression mostly by untrained artists. You know, I've done a lot of research, when I was writing the book. In the early 1990s, Aron Packer had a photo show at the Chicago Cultural Centre of his photos of these carvings. And that was the most attention they had ever received. Even after that, they hardly got any attention. So, I just decided when these things started disappearing, first of all that I had to document them, which I was late to the game on as a lot of them had already been destroyed before I started photographing them. And how could I get publicity, and I just concluded maybe a book would be the way to get some attention. The problem is that the topic is of limited commercial appeal. So, I worked with Aron Packer. I wrote the book and did most of the work, but he contributed a lot of photos, and then we worked with a designer who did a great job, I thought, designing and publishing the book in 2021.

Jennifer: Great. I'm going to come back to a couple of questions that I missed from earlier. Do you have an exhibition in this field that you think has been particularly important to kind of pave the way?

Bill: Well, I thought about that. I didn't see the Corcoran show [which many people mention] as that was before I had really connected and I was living in California when that show was around. The show that really mattered to me personally was in 1977, Claus Oldenburg’s Mouse Museum, and Raygun Annex. I don't know if you're familiar with that? In 1977, it was this structure that Oldenburg filled with his collection of vernacular expression,basically. I was pretty young then, I was 21, and started collecting pop culture objects, and Japanese robot toys were an early interest. And so, to walk through Oldenburg’s collection -- this contained a space full of his collection of the same kind of stuff -- was very validating and also showed that there was a more aesthetic dimension to this than maybe had occurred to me previously. And then a similar show was Jim Shaw's thrift store art show, which he toured in the early 90s, and Intuit actually sponsored its Chicago stop in 1991. I didn't know anything about Intuit at the time, but I was already collecting thrift store art and so that show really made me focus even more on trying to acquire that kind of art.

Jennifer: How long have you been on the board at the Intuit Outsider Art Museum in Chicago?

Bill: Probably about since about 1994. So, not a founder but I was there from early on. I've been on the board for a long, long time. I was president for a couple years.

Jennifer: What do you see as some of the main goals now for Intuit?

Bill: Well, it certainly has changed, meaning now that the big museums are finally starting to show this kind of work. That represents a challenge for Intuit. Even in Chicago, we're no longer the exclusive exhibiter of this, although the Art Institute is still hit and miss. They took the James Castle show that toured; they mounted the Yoakum show, which was great. From our point of view, we have a fair amount of pride in our standards, which I think are [more focused] than other museums.

Two bottle-cap figures originally in the collection of Herbert Hemphill

Jennifer: And, on the notion of terminology, is there a phrase you would prefer to use or that you use for your collection?

Bill: Well, I consider myself as something of an agnostic. I wished we still called it folk art, which, when I started getting interested, it was what my friends called it. I totally understand why the ‘folklorists’ said it’s not folk art, and they are right, it’s not. I’ve spent way more time than I think is productive, writing and arguing and talking about terms. So that’s why I’m an agnostic, I don’t really feel strongly about it all. I think Outsider art is a perfectly good term when you understand it in a certain way, which is to say, it’s made outside of the mainstream art world and outside of the normal channels of the dominant art market. I also understand why other people don’t like it. My conclusion is that every term is problematic.

Jennifer: My last question is: are there any individuals that you think paved the way for success in this field?

Bill: That’s a tough one. I mean, there’s so many. I guess the founders of Intuit. Obviously, Herbert Hemphill who I feel I have a personal connection with even though I never met him. I guess I think the right thing to say would be the artists, people who made the art. People like Eugene von Bruenchenhein or Henry Darger who laboured in obscurity and created this incredible stuff. But the field itself, and this is where one of the things I think is fraught particularly when people are talking about outsider the term and the elitism and all that. The field was created by collectors, artists, and curators. It wasn’t created by the artists themselves. The artists, by definition, are just these people who are just making stuff. Some of them made stuff to sell, but certainly were pretty much just making stuff from their point of view. It was the collectors and the artists who really created the field.

There are people who are important in Chicago who are important to me but not necessarily in the field, although, an example of unsung heroes is one of my friends. You may or may not have run across him on social media, a guy named Dan Pohl. He is a friend and an amazing collector of self-taught art from the 1980’s. Amazing because he never had any money. He collected incredible art, sold it over the years, including a lot to me. He’s somewhat obsessive, so he spent years collecting images of self-taught art off the internet and now he posts them on Facebook on a frequent basis. He’s got a great eye, he was a great collector, he is a great collector. He also makes great furniture.

Jennifer: Thanks Bill.

Bottle-cap bunny by Clarence and Grace Woolsey, 1960s