doug robson, san francisco – MEET THE COLLECTOR PART SEVENTY five

I’ve met Doug Robson several times at different events across America, and having known about his family’s show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington) in 2022 and accompanying catalogue, it felt apt to pin him down and find out more about his and his mother’s collecting habits of self-taught and outsider art. Delve into part seventy-five of my Meet the Collector series with Doug Robson from his San Francisco home…

Doug Robson and his mother Margaret

Jennifer: Briefly, what is your background and what year would you say you seriously started collecting art?

Doug: My background is as a trained journalist. I worked as a business reporter for a few years, and then I switched over to doing sports. I was writing about and covering professional tennis around the world for 15-20 years as a beat reporter. More recently, I have been working on a book project that has to do with tennis. Since I left tennis beat reporting, some of my energy and time has gone into my family’s art collection and dealing with some legacy projects that I needed to attend to. But I don't really have any formal training in art, or art management, or art collecting. I seriously started collecting probably in 2015/2016 - a couple of years after my mother died. It was around this time that I donated the bulk of my mother’s collection to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. I had to figure out what to do with the collection my mother had left behind because she hadn't really given me very specific instructions about what she wanted to have done. And in that process, I think I got energised and enlivened by art in a way that I hadn't been before.

Jennifer: I bet your mother had a chuckle about that and leaving it with you to sort! So obviously you've said you got into this art through your mother, can you tell us a bit about your mother Margaret for those who don't know, and why she was so passionate about this art?

Doug: That’s a long story but I’ll try to keep it brief. My mother grew up in sort of semi-rural Minnesota from a humble background. She was raised by her mother, my grandmother, who was divorced and who raised four kids whilst teaching piano. My mother really had little exposure to art or museums growing up. Then she went to college, eventually moved to Chicago, and started to have a successful career in banking as a young woman. Then she met my father and got married. Art was a joint endeavour for my parents, and they started to decorate their homes as they moved around. They collected antiques and Americana, weathervanes and duck decoys. I think that's how it all started.

When my father was off working my mother had a little bit more time to explore. She got involved with some pickers out there in the world in different places and they were helping her source folk art and outsider art. When my father passed away it really became her raison d'etre. It took over her attention and focus for the last stretch of her life.

Doug within the ‘We are made of Stories’ exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Jennifer: You donated a lot of her collection to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington as you said. You chose it because of the free entry and that there was a curator there (Leslie Umberger) overseeing that side of their collection. Were an exhibition and book always going to be on the cards when that happened?

Doug: Yes, it was part of the understanding that the exhibit would be part of the arrangement for the gift and the donation. And, yes, for all the reasons you mentioned. I so appreciate museums that are free, as it just opens up the world where you can walk into a place and be exposed to things you might not otherwise see. You can poke your head in and see new things. And I love that about the Smithsonian Institution. My family had spent some time in Washington D.C., and some of my youth was spent growing up there. Leslie Umberger had known and worked with my mother. There were dedicated gallery spaces for self-taught and folk art and outsider art at the Smithsonian, which have been reconfigured subsequently, so all those elements made it feel like it was a good fit.

Jennifer: Great. So, once you had your mother's collection after she passed away, you donated some. Was there a piece that you kept that was your favourite piece from her collection, and a piece that you donated that you loved?

Doug: Well, everything that was in the exhibition will eventually go there as promised gifts, but there were pieces that came back to live with me for now. I mean, there were a couple of things my mother gave me before, and there are a couple of things that I doubt I will give to the museum before I'm gone from this world. What sticks out? Certainly, the Ulysses Davis ‘Uncle Sam’ is a piece that was in the show and lives with me now. And I don't expect it will be anywhere but with me until I'm gone… It's such a beautiful work. It speaks to Davis' patriotism and his pride at being American, but it also references his pride in being African American because the figure is very dark, it doesn't look like what we see in the normal Uncle Sam depictions.

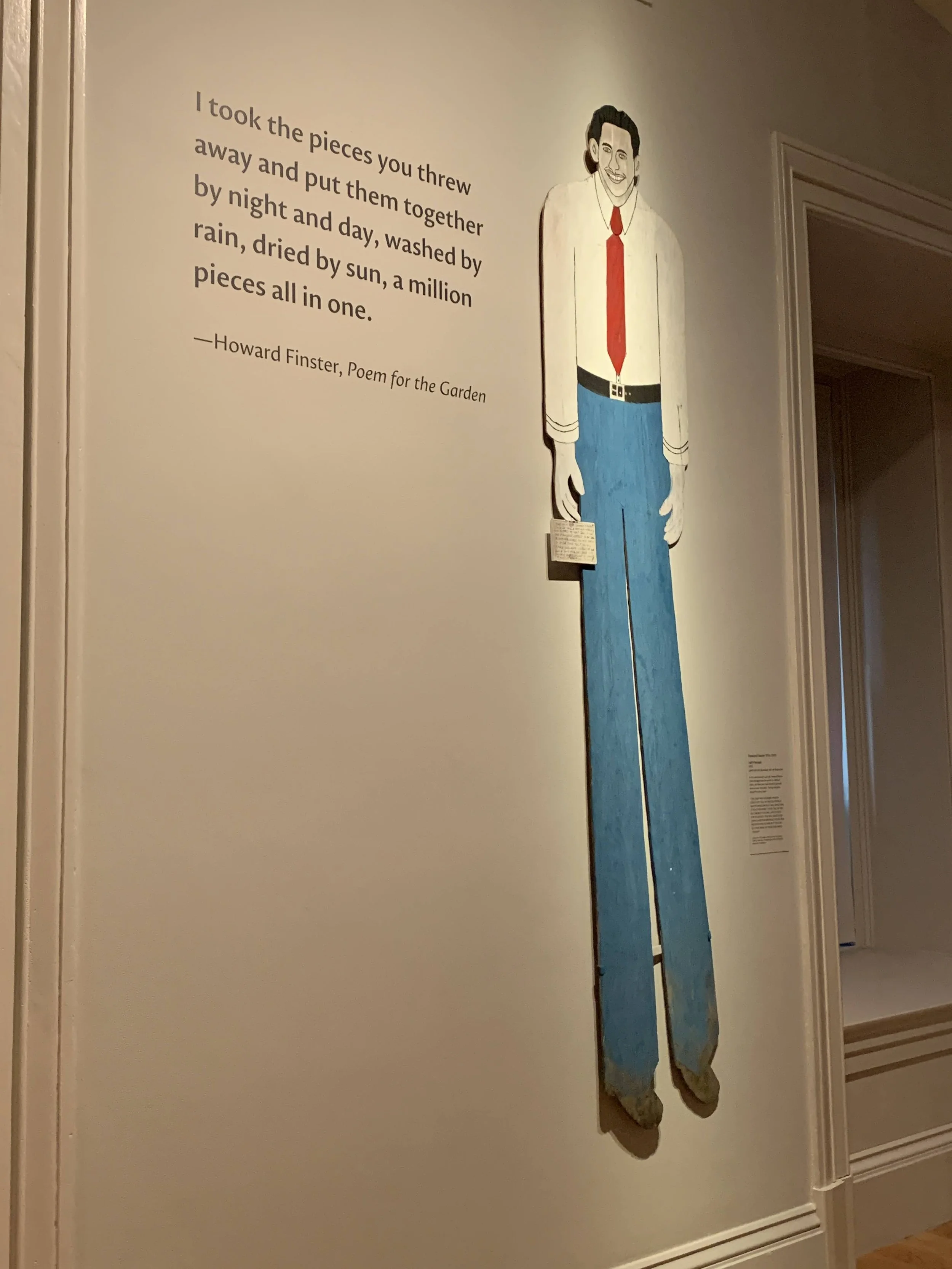

The other one that I was thinking about is a very tall Howard Finster man. It's a self-portrait. It's giant, around eight or nine feet tall with a little placard he's holding. It sort of describes how he was the only one that could make himself big in this world. And I love the bravado in it and the self-actualisation that's built into it -- like if I if I'm going to be something in this world, I'm going to have to do it myself, I'm going to have to make myself big! There's something very American about it.

Ulysses Davis’ ‘Uncle Sam’ with painted and carved wood, 1976. Collection of Douglas O. Robson from the Robson Family Collection, Promised gift to the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Jennifer: Brilliant. Is it numbered as an early piece?

Doug: It's not numbered. I don't remember the year exactly. The last I’ll mention that I donated are the Albert “Kid” Mertz railroad spikes – just a giant pile of railroad spikes that the Michigan-based artist painted with little faces. There was just something so folky, carnival-like and joyous in them. They would sit in a pile in my mother's house and kids would come over and they'd pick them up and they'd want to play with them. They were a total magnet. It always got a reaction out of people, and it was very whimsical in a way that I think my mother appreciated.

Jennifer: I saw that photo in the book, and I was wondering if that work ever got displayed anywhere in your mother’s house because there's quite a lot of them! And then from your collection now do you have a favourite piece or a favourite artist?

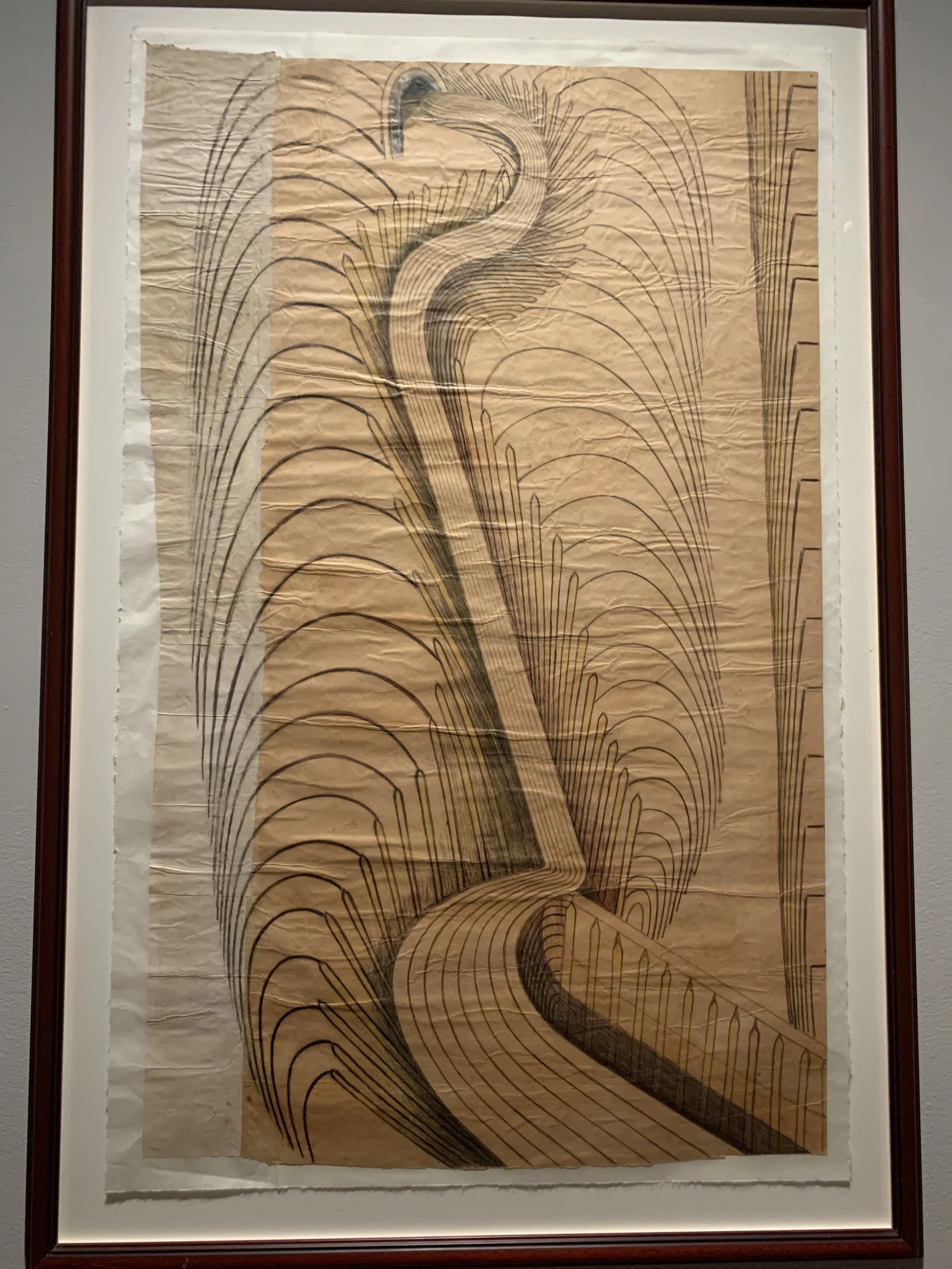

Doug: I struggle sometimes with favourites. People would often ask me that as a tennis reporter… who's your favourite player? As a journalist, there are certain players I love to watch because they were beautiful players. But also, working as a journalist, it was also what the dynamic was with interviewing them and the insights they might offer. But among my favourite artists are Martín Ramírez, Judith Scott, Bill Traylor and Anna Zemánková. Martín Ramírez speaks to me because he was a migrant to this country. He lived in California, like I do, where he was incarcerated, probably against his will, for being schizophrenic. And so, there's something magical about what he did with the materials he had available to him, which were, you know, not plentiful, but also just this mystical world of Mexico that he created with caballeros and tunnels and trains that was entirely born from within himself. I've always been very drawn to his work. I think it's just beautiful and profound.

Martín Ramírez framed work. Collection of Douglas O. Robson from the Robson Family Collection, Promised gift to the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Jennifer: Definitely. And it's nice to have a progressive studio-based artist on your list, Judith Scott! I read in your book that you used to visit Creative Growth. Did you go there with your mother?

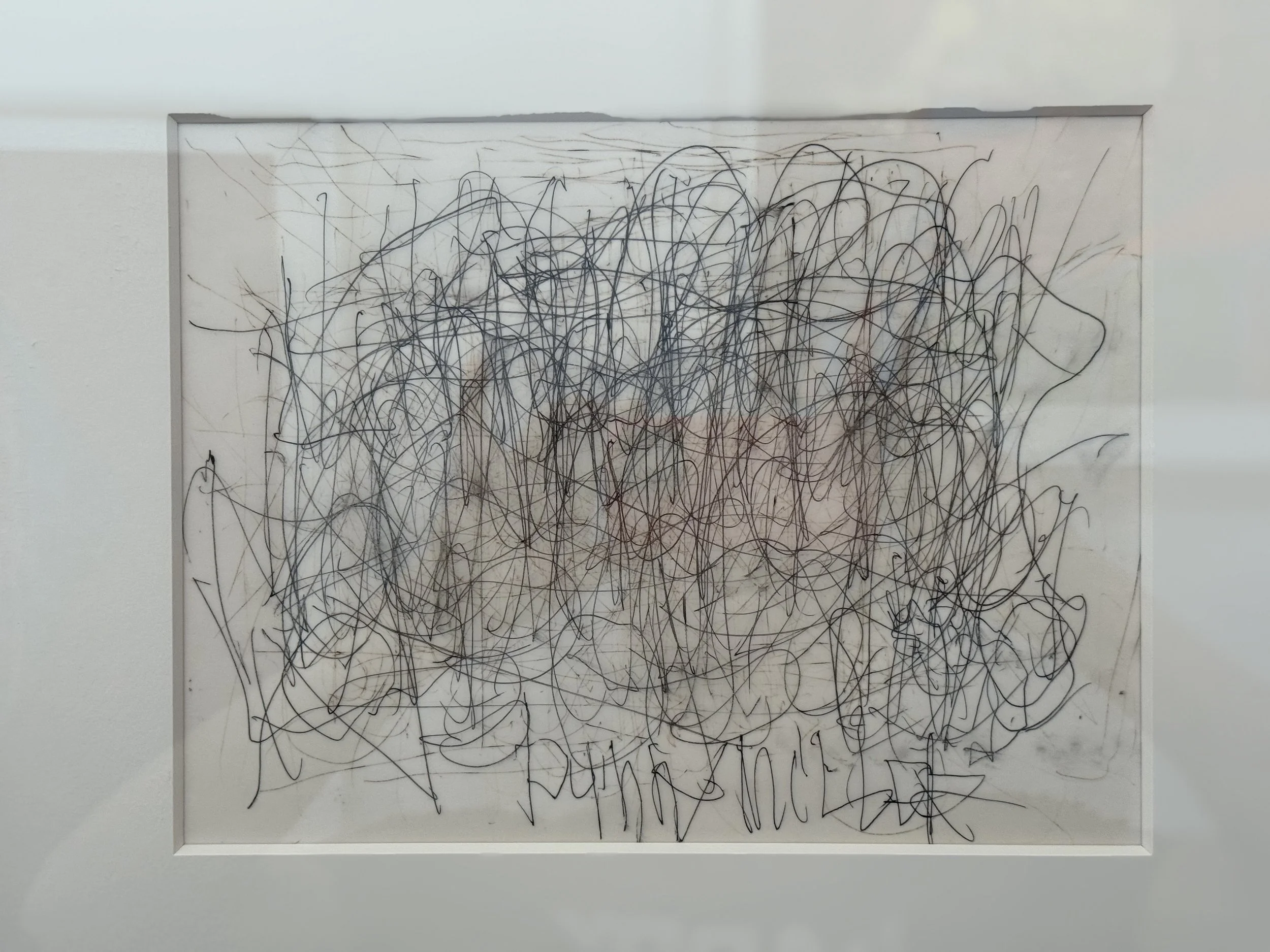

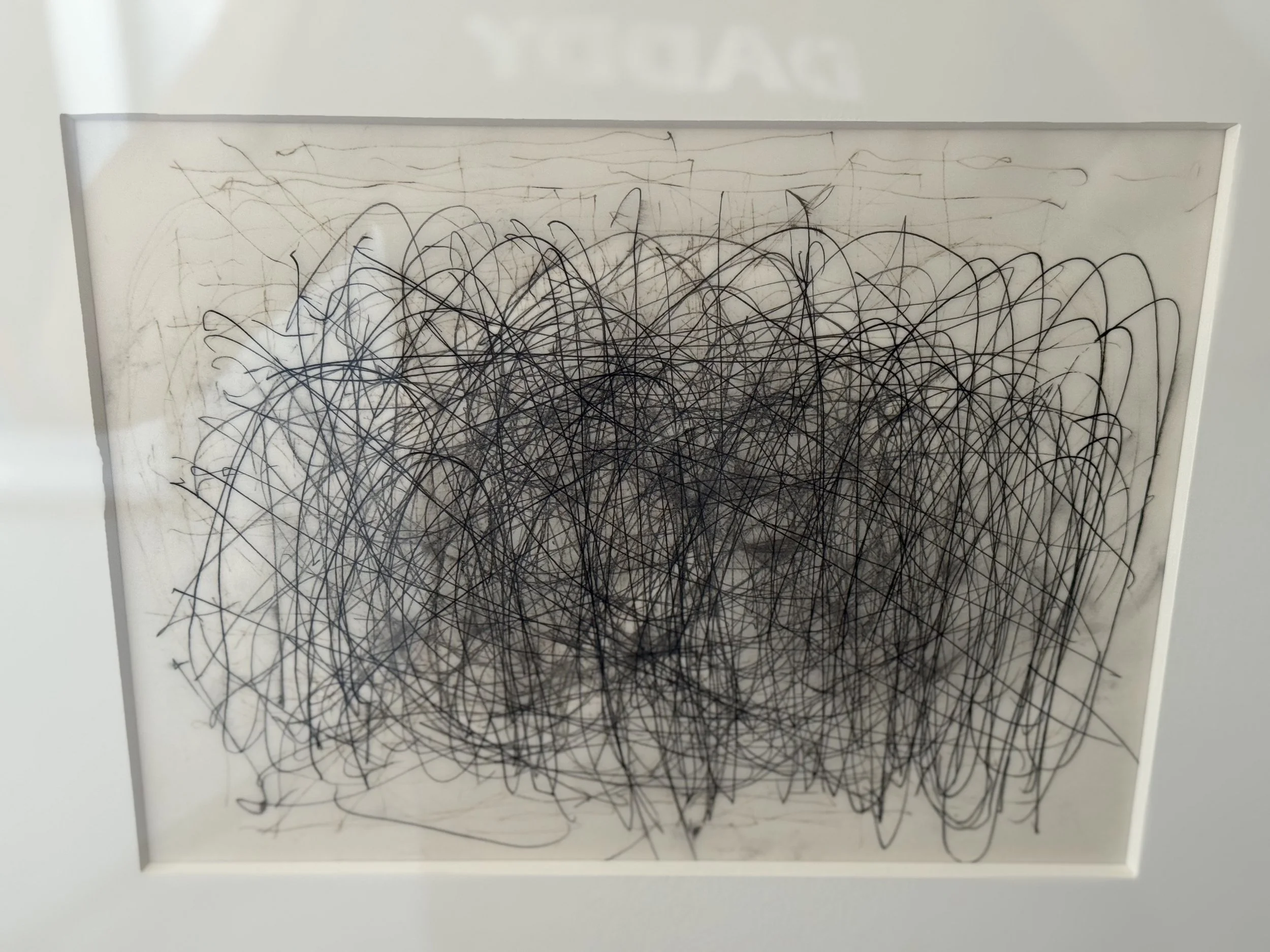

Doug: Yes, so my parents at some point lived in San Francisco. A friend of mine turned them on to Creative Growth. My parents went there and thought it was amazing and I started to go with them occasionally, to their events. Indeed, my first art pieces were from Creative Growth - I have two little drawings from Dan Miller, which might have been the first things that I ever bought, and done with such force. They're pencil, but they're very vigorous and dark and they look like wire almost. I still have those. You’ve been to Creative Growth right?

Jennifer: Of course! Quite recently at the end of 2025 too.

Doug: The energy with the artists all working collaboratively and the gallery right there, there's something very organic and really special about that because I think we often conceive of artists as being alone in their studio, but there's something very different about the dynamic there.

Jennifer: Did you meet Judith before she passed away?

Doug: Sadly no.

Jennifer: Then you've got Anna Zemánková on your list. It's quite rare when I interview Americans that they talk about European artists, so, what is it about her work that draws you in?

Doug: I was exposed to her work on a trip with Creative Growth to the Art Brut Museum in Lausanne in 2016/2017, and they had a show of hers up. It just blew my mind, it's so beautiful. It's so organic, but these are not real, they come from the imagination.

Jennifer: They are beautiful.

Doug with Judith Scott’s work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Jennifer: So, when I read about your collection, you said it's mainly American artists or those whose lives and works powerfully embody American experience, but are there any other European artists in your collection or on your hit list?

Doug: I definitely see things that I would love to bring into my collection. I think I have been focusing mostly on American artists not only because I live in America and it's more accessible for me here, but you know I think my vision is that everything will live together one day at the Smithsonian in my family’s collection. But trust me, there's a lot of things I would love to bring into my life. If there’s something I really would love to add to my collection, it is an ACM. I've always been fascinated by those architectural constructions that are so intricate and minute and using found materials. They seem to be speaking about something I don't quite understand, but that I really am drawn to. It's just that they're so fragile and there aren't a lot in America. I really worry about the shipping involved with bringing one of those here, but maybe one day!

Jennifer: I am sure one will turn up at the Christies New York Outsider Art auction one year! Have you heard of or been to Gugging in Austria?

Doug: I’ve never been, but I’ve accessed Leopold Strobl’s work in America and I love his work. I think he produces a work every day. They’re arresting and I think they look fantastic when multiples are grouped together.

Jennifer: I agree, and there were some grouped in a row together at the last Venice Biennale which looked impactful. Right. How many pieces would you say approximately are in your collection? And are they all out or do you keep pieces in storage?

Doug: I don't know exactly, more than 75, less than 200? I haven't recently done a count. I still have my mother's apartment in New York so there are things there as well. I have a few things in storage, but I really don't like putting things in storage. There are a few works on paper that need to be rotated a bit here and there, but I'm not as stringent as a museum would be. I also tend not to be a salon-style hanger; I like things to have space to breathe and live. I think I may do a big rehang in the next year or two because I've found that that really can breathe new life into a collection when you see it in new places and you give it different juxtapositions.

Jennifer: Rather than just getting something new and saying that's the only gap it's going to fit in, so it has to go there! Ha. Good luck with that. Do you collect anything outside of the outsider, folk art realm or are you very focused on that?

Albert “Kid” Mertz railroad spikes (close-up). Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Margaret Z. Robson Collection, Gift of John E. and Douglas O. Robson

Doug: I collect a little bit outside of the self-taught, outsider art world. I've also had a couple of things commissioned by a contemporary artist. I met a French guy named Joanathan Besacci and got him to do a collage of all of my press passes and the lanyards from all my years reporting. I also had him take some maps that I had because he has done a lot of collage style things with maps and construct a portrait of an African-American tennis player named Arthur Ashe, who was kind of a hero of mine. So, I do, but only a small portion.

Jennifer: As a side question, are you good at tennis yourself?

Doug: I was decent back in the day. I played some juniors at the national level and I participated in Division I in college tennis here in America. But I'm not playing much tennis these days as I’ve mostly been doing triathlons for the last 15 years.

Jennifer: Well, that's amazing. Back to art! Do you have a particular style that you're more drawn to? Is it painting, textile, ceramic, or is it generally anything that just piques your interest?

Doug: I wouldn’t say I have a particular medium that I'm drawn to. I have sculptures, works on paper, drawings, paintings. I saw two exhibits in the last year or two, exquisite embroidery exhibits, that really caused me to want to know more about textiles and maybe add some to my collection. One was the Madelena Santos Reinbolt exhibit at the American Folk Art Museum, and then there was an Amish quilt exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. And they really blew me away. I was much more drawn into it than I thought I would be. I definitely do not go into collecting thinking like I'm going to get ceramics or I'm going to get, you know, a work on paper. I must have a visceral reaction to something usually.

Jennifer: It mentions in your book about the 1982 Black Folk Art in America exhibition being a source of inspiration for your parents, and many other collectors have noted that same exhibition too. But is there an exhibition in this field since you’ve been collecting that you felt has been really important?

The large Howard Finster mentioned earlier, hanging in the show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Collection of Douglas O. Robson from the Robson Family Collection, Promised gift to the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Doug: For me, as a fairly newbie in all of this, the Bill Traylor ‘Between Worlds’ exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum was a really important exhibit for the field. It was obviously very critically well received, but I think it really pushed the art a little bit more into the mainstream than it had been, for better or for worse. I feel like it really put Traylor on the map and it certainly created an art market environment where galleries like David Zwirner started selling that art. It was a big wave in the longer historical arc of this art being more recognised and in the mainstream. The other one I would say was last year's exhibit of Creative Growth artists at SFMOMA in San Francisco. I think was a really important step regionally for the West Coast, and for bringing to the fore an incredible studio/art gallery and disabled/neurodivergent artists.

Jennifer: Definitely, 100%. That was one of my questions as I know your mother liked the work coming out of progressive art studios. Do you go around many other progressive art studios, or have you only really been to the Bay Area ones?

Doug: Yes, I've only been to the Bay Area ones. I wish I could say I'd been to a lot more or that I have found the time and the resources to do that.

Jennifer: Next time you’re in New York, schedule in some time! So, when your parents were living in Chicago, Carl Hammer was someone that they met early on and they had conversations together. Who do you think in terms of individuals, since you've been collecting, who are kind of pivotal in kind of helping with where things are at now?

Doug: I would say, in my roughly 10-year dive into all of this, Tom Di Maria from Creative Growth. His impact at Creative Growth in the time that he led the organisation in the last couple of decades was pivotal for disabled and neurodivergent artists. It was and has become the model for other similar organisations around the country, maybe around the world. So, I think Tom really has been pivotal for the field. I also think, closer to your neck of the woods, Bruno Decharme and his massive gift to the Pompidou. That's a landmark donation that I think will shape the field for in Europe for some time to come.

Jennifer: Did you get to see his show of the collection at the Grand Palais in 2025 whilst the Pompidou was closed?

Doug: No, I didn't see the show, unfortunately. But on that tour that I told you about with Creative Growth back in 2016/2017, we were able to go to the ABCD collection space (where Bruno’s collection is held). It was stunning.

Jennifer: His collection truly is. Do you buy most of your work from galleries, auctions, the artists, or are you one of these collectors that does lots of swapping with other collectors?

Doug: I'd say it's pretty rare that I have a direct conduit to an artist, which I think is harder to develop these days than say when my parents were collecting. For the most part I go through galleries and auctions. I haven't been a big swapper. I swap a lot of conversations with people, but not a lot of actual art swapping. I am doing it on my own more or less.

Jennifer: And that’s fine!

Early Dan Miller purchase

Early Dan Miller purchase

Jennifer: You've said that you wanted to add an ACM work one day. Are there any other artists that you're thinking like, oh my god, I really want one of those one day?

Doug: I mean, another European, Marcel Storr. I would really love to have one of those in my life.

Jennifer: Oh my god, Beautiful.

Doug: I think there will be a more of an international phase of my collecting, but I came out of the experience of my mother's collection with an intent and a focus on American artists. I think that that could change and evolve.

Jennifer: Good to hear. How do you feel about the term outsider art? When you describe your collection to someone, do you say it's like a self-taught or an outsider art collection or something else?

Doug: I think there isn't a great catch-all term for this art, but I mean, isn't that kind of indicative of the art itself? I mean, it's hard to categorise, hard to define. I grew up with the term outsider art, and I think for reasons, probably conscious and unconscious, I generally refer to it as self-taught art now. I will often say it's self-taught work and describe what that means but also use outsider art because I still think it is more commonly understood as a term. The art is in the margins and it's outside the margins. It's in the mainstream and it's outside the mainstream. I don't think I've heard a term that is a home run definition, as we say in this country. But, you know, the human mind is a categorising, meaning-making machine so it makes sense we want to categorise art in some way, in the same way we want to organise our cupboards, right? But I generally use self-taught because I feel like it's a little bit broader, which makes it murkier, but it's also less charged for some people.

Jennifer: Yeah, that makes sense, and I use the term self-taught too. Finally, is there anything else you’d like to add?

Doug: For me, as I think it did for my parents and my mother, the story of the artist is integral and important to me in the art I collect because I feel like it informs the art. It gives it a lived, experiential quality that for me enhances the experience. I find in my own collecting that the art has to stand on its own, but knowing how it came to be is also important in how I enjoy, experience, and understand the art.

Jennifer: And, what keeps you buying art today?

Doug: Having a reaction to a piece of art, adding to my parents’ legacy, and building a collection of my own. It's a journey, it ebbs and flows. I’m paraphrasing here, but I think David Rockefeller said it well, along the lines of: … I don't think of myself as a collector, I'm a custodian. These things are going to live longer than I'm going to live. And my hope is that these pieces that outlive me, will not outlive the imagination of those that get to experience them in the years ahead and maybe enhance their understanding of their world or, you know, often the American experience, which is always changing and evolving.

Jennifer: That's a nice way to end and thank you very much for your time.